History of Anaesthesia

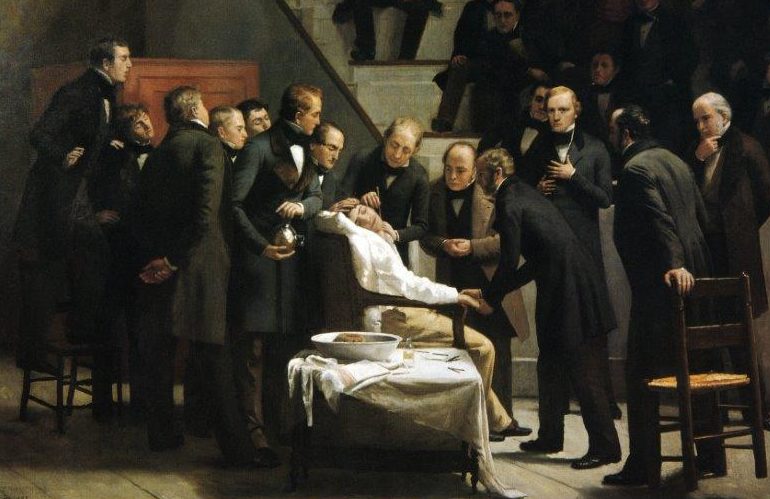

Although many individuals administered anaesthetic agents in the decade 1835-1845, they were not widely publicised and did not impact on general medical practice. On 16 October 1846, at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, the first public demonstration of ether anaesthesia took place.

The anaesthetist was William Morton and the surgeon was John Warren; the operation was the removal of a lump under the jaw of Gilbert Abbott. Present in the room was another surgeon, Jacob Bigelow, who wrote a letter to a friend in London which described the process. This letter was carried on the mailboat SS Arcadia, which docked in Liverpool in mid-December 1846.

On 19 December 1846 in both Dumfries and London, ether anaesthetics were given. Few details are available about the Dumfries anaesthetic, but it is believed that the patient had been run over by a cart and required an amputation of his leg; it is also believed that the patient died. In London, at 52 Gower Street, the home of an American botanist Francis Boott, a dentist named James Robinson removed a tooth of a Miss Lonsdale under ether anaesthesia. Two days later at University College Hospital, Robert Liston amputated the leg of a chauffeur, Frederick Churchill, while a medical student called William Squires gave an ether anaesthetic.

It is difficult to understand today how major this advance was. Before this, surgery was a terrifying last resort in a final attempt to save life. Few operations were possible. Surface surgery, amputation, fungating cancers and ‘cutting for stone’ (the removal of bladder stones) were really the only areas in which the surgeon could practice. The inside of the abdomen, chest and skull were essentially ‘no go’ areas. Speed was the only determinant of a successful surgeon. Most patients were held or strapped down – some would mercifully faint from their agony – many died either on the table or immediately post-surgery. The suffering was intense.

Liston, an eminent surgeon, was once operating for a bladder stone. The panic stricken patient finally broke loose from the brawny assistants, ran out of the room, down the hall and locked himself in the lavatory. Liston, hot on his heels and a determined man, broke down the door and carried the screaming patient back to complete the operative procedure (Rapier HR. Man against Pain London 1947;49).

A grimmer tale is told in the New York Herald, 21 July 1841, of an amputation:

‘The case was an interesting one of a white swelling, for which the thigh was to be amputated. The patient was a youth of about fifteen, pale, thin but calm and firm. One Professor felt for the femoral artery, had the leg held up for a few moments to ensure the saving of blood, the compress part of the tourniquet was placed upon the artery and the leg held up by an assistant. The white swelling was fearful, frightful. A little wine was given to the lad; he was pale but resolute; his Father supported his head and left hand. A second Professor took the long, glittering knife, felt for the bone, thrust in the knife carefully but rapidly. The boy screamed terribly; the tears went down the Father’s cheeks. The first cut from the inside was completed, and the bloody blade of the knife issued from the quivering wound, the blood flowed by the pint, the sight was sickening; the screams terrific; the operator calm’.

The introduction of anaesthesia changed all of this. Surgery could slow down – become more accurate and could move into ‘forbidden areas’ of abdomen, chest and brain. The evolution of surgical practice has been dependent on anaesthesia and the concomitant introduction of antisepsis through Lister’s carbolic spray.

Once ether was used then further inhalational agents were introduced. Chloroform was introduced by the Professor of Obstetrics in Edinburgh, James Simpson, in November 1847. This was a more potent agent but it had more severe side effects. It could precipitate sudden death, particularly in very anxious patients (the first of these incidents happened in early 1848) and it also had the potential to cause late-onset and very severe liver damage. However, it worked well and was easier to use than ether and so, despite its drawbacks, became very popular. Over the next 40 years a large number of ‘smelly agents’ was introduced, each with perceived advantages, but few withstood the test of time. The next major advance was the introduction of local anaesthesia – cocaine – in 1877. Then came local infiltration, nerve blocks and then spinal and epidural anaesthesia, which in the 1900s allowed surgery in a relaxed abdomen without the huge ‘depth’ of anaesthesia required by ether and chloroform. Newer, less toxic, local anaesthetic agents were introduced in the early 1900s.

The next important innovation was the control of the airways with the use of tubes placed into the trachea. This permitted control of breathing and techniques introduced in the 1910s were perfected in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Then came the introduction of intravenous induction agents. These were barbiturates which enabled the patient to go off to sleep quickly, smoothly and pleasantly and therefore avoided any unpleasant inhalational agents. Then in the 1940s and early 1950s, there came the introduction of muscle relaxants, firstly with curare (the South American Indian poison!) and then over subsequent decades a whole series of other agents. Curare in the form of tubocurarine was first used in clinical anaesthesia in Montreal in 1943 by Dr Harold Griffith and first used in the UK in 1946 by Professor Gray in Liverpool. In the mid-1950s came halothane, a revolutionary inhalational agent, which was much easier to use. All of these groups of drugs have since been refined so there are now much more potent and less toxic intravenous agents, inhalational agents, local anaesthetics and muscle relaxants. Anaesthetists are now highly trained physicians who provide a whole range of care for patients – not just in the operating theatre. They are usually consulted in the preoperative period to optimise the patients’ condition and they usually run High Dependency and Intensive Care Units. They are involved in obstetric analgesia and anaesthesia, emergency medicine in Accident and Emergency Departments, resuscitation, major accident care, acute and chronic pain management and patient transfers between hospitals.

Anaesthesia is now very safe, with mortality of less than 1 in 250,000 directly related to anaesthesia in most high income countries. Nevertheless, with today’s sophisticated monitoring systems and a greater understanding of bodily functions, the anaesthetic profession will continue to strive for improvement over the next 150 years.

Reproduced by kind permission of Dr David Wilkinson, President of the WFSA

For a full history of anaesthesia, from 4000 BC and covering Babylonian, Greek, Chinese, Arab and other extraordinary contributions to the development of the profession and to patient care visit the interactive timeline at the Wood Library Museum website.

The history of anaesthesia in Argentina can be explored in FAAAAR’s virtual museum: